The thing I find most rewarding about this series is taking journeys down the rabbit holes. If I was just doing a straight reading of the Quran, I would pass by these moments with only fleeting thought and probably leave my reading with just a dismissive, “whatever,” as I have seen in the reactions of many other people who have read the Quran. But by writing a post I am forced –or rather, encouraged– to stop, look, and put some effort into understanding the material. There are a number of great resources available for reading the Quran, resources that help interpret the language and tradition, and in consulting these resources I enjoy getting to sit in another culture and trace its puzzles and eccentricities. Within Surah al-Hajj there were a lot of little moments where I read something, paused and went, “…huh,” before reading forward further. I noted these things down, but then didn’t find a place to include them in my last post.

So today is going to be my inventory of all the little things that made me go, “…huh.”

Ayah 5

In declaring the Resurrection and Judgement, the surah naturally includes a defense of God’s mastery over life and death. We’ve seen the descriptions along these lines before, but today I wanted to stop upon ayah 5 to consider the two different evidences it gives for God’s control over life.

Ayah 5 asserts God’s involvement in the life-cycle of the human being paying particular attention to the phases of gestation. The process is sequenced thus: dust (generally taken as a reference to Adam’s creation), a bit of semen, a clinging thing, a quasi-formed lump of flesh, then a child upon birth. Notice the phases of gestation are elaborated more than post-birth phases (only mentioning child-adult-senior). This asserts God’s influence in the unseen phases of life, which serves to exemplify His knowledge and power over the things unknown to men. The given sequence of gestation is fine, and Muslims apologists enjoy the ease with which this language fits modern knowledge, but I will mention that the more modern additions to our knowledge of gestation –the female contribution– is not mentioned. The male contribution to reproduction is something even the most ancient portions of the Hebrew Bible assumed (the word for semen is “seed” and the same word for the horticultural term), and so the Quran is not unprecedented in associating semen with gestation. Elsewhere, the Quran has represented the woman as a field to be plowed, suggesting she’s seen more as a receptacle that fosters the seed into life. I do not know historical theories of gestation (that information is harder to find than historical theories of cosmology) so I cannot confirm what the people around Muhammad’s time thought gestation involved. At any rate, this passage does not run afoul of modern science and that is enough. The purpose of this image is more to assert God’s involvement in forming life and then unforming it –whether through death or senility– and thus asserting God’s dominion over this subject.

That prior image asserts God’s command over the rise and fall of the life cycle. For the process more direct to the idea of resurrection, the surah cites God sending rainfall to bring forth plants (this is also so in ayah 63). We have seen this image before several times, but I never thought of it as more than a boast of control and divine flexing.

Then I realized that I’m the wrong audience for this imagery. I live in an area that not only gets regular gentle rain, but also has year round vegetation. Ayah 5 specifically mentions that the earth was barren, but that it transforms upon God sending rain.

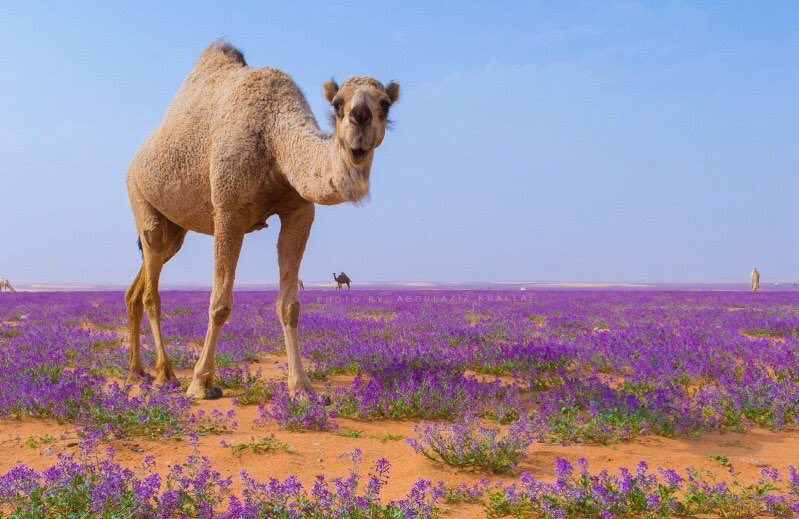

Saudi Arabia is mostly desert, including the Hijaz region where Medina and Mecca are situated. Rainfall there is rare and unreliable for most farming purposes. Just as in deserts across the world, the plantlife of Arabia has adapted their life cycles accordingly. Many plants developed resilient seeds that can lay dormant for long periods of time. When a large enough rain comes, the seeds grow into a fast-growing plant with just enough life cycle to generate the next batch of seeds for the next eventual rain. This phenomenon is called a desert bloom. For a short time after a good rain, the barren deserts of Saudi Arabia bloom. You see a dry world that looks like this:

Transform to something like this:

Check out these photo collections: 1, 2.

So from this standpoint we can see how rainfall would visualize the resurrection to the Quran’s original audience. Agriculture in Saudi Arabia is not strictly dependent on rain (except for in Yemen and the south where rains are more seasonal and predictable). Instead, the majority of population centers were established around springs and wells. Water for living mostly came from the ground, less the sky, and it was a resource to be rationed and controlled by people. It was tamed. Rainfall on the other hand is potentially dangerous in combination with the Arabian soil, resulting in scouring flash floods and sinkholes. I imagine that the rocky mountain passes of the Hijaz region are nightmares during a good rain. Yet the rain also yields this beautiful bloom of life in its aftermath. What an apropos metaphor for the Day of Judgement. I’m surprised the Quran hasn’t used it more.

Ayah 15

Starting in ayah 11, we are told of fair-weather believers who, when times are rough, turn to polytheism (presumably because they do not trust God to be enough or because they think God is apathetic to their plight and thus seek an intermediary). The ayat continue on to rebuke their actions and insist that God has Paradise prepared for the faithful. This culminates in ayah 15, which I’m going to translate as follows:

Whoever thinks that God will not help him in this world and the hereafter, so let him extend a rope to heaven then let him cut, so let him see: will his plan remove what enrages?

Enraged? The people we were contemplating as of ayah 11 were despairing, not enraged. But this is not as jarring inasmuch as the interpolations that Sahih International adds into their own translation:

Whoever should think that Allah will not support [Prophet Muhammad] in this world and the Hereafter – let him extend a rope to the ceiling, then cut off [his breath], and let him see: will his effort remove that which enrages [him]?

What?!? This ayah is goading someone to commit suicide?!

So a few comments about this translation. Sahih makes the assumption that the object of the verb “help/support” is Muhammad. This isn’t a bad assumption; when the Quran refers to a singular “you” we have basically always assumed it was talking to Muhammad and it’s equally reasonable that a singular “him” would also refer to Muhammad. But all the following verbs talking to this doubter are also singular, so the use of the singular pronoun does not stand out as referring to a separate entity. This ayah potentially is goading a hypothetical doubter about his own trust in God’s provision.

Then there’s the word translated as “ceiling.” That word, samaa’, usually gets translated as “heaven” or “sky” in other places (scroll down this concordance for Sahih’s preferences). Scientifically at that time the people did consider the sky to be a ceiling above the earth, so the ideas are linked. My search for occurrence of the word “ceiling” in the Quran did yield one result which is an ayah referring to the creation of the heavens. There is also a chance to calculate in old theories that above the firmament was the heavenly realm where God (whose presence is represented through mentions of His throne) and the spiritual angels resided.

Then there is the word yaqṭaʕ, “cuts off” or “interrupts,” which is a little hard to make sense of because the verb has no object. What is being cut off or interrupted? A piece of the heavenly ceiling? The rope? Muhammad’s ministry? God’s support? The man’s own life/breath?

Any of these possibilities can be mixed or matched to reach different interpretations. One is that the Quran is taunting a man who does not trust in God to then reach Heaven through his own effort, i.e. extending a rope to heaven and cutting his way through the ceiling, which is an impossible task. The man is both riddled with doubts and also frustrated/enraged by his circumstances, so this idea makes sense of both emotions mentioned in the passage. Another possibility is that the man –frustrated by Muhammad’s success, not convinced such will last, but impatient for it to end– is being taunted with the impossible task of climbing heaven to cut off Muhammad’s connection with God at its source. And lastly, there is the idea that –whichever the nature of the doubt– the Quran’s solution is that the man should extend a rope to the ceiling and strangle himself.

So the boiling down of your options are that the Quran is either saying “ha, good luck with that” or “maybe try hanging yourself.” Many scholars whose thoughts contribute to the traditional interpretation of the Quran (Majma‘-ul-Bayan, Tibyan, Al-Mizan, Fakhr-i-Razi, Abul-Futuh, Tafsir-us-Safi, Mujahid, Ikrimah, Ata’, Abu Al-Jawza, Qatadah) have given weight to or endorsed the latter, which is why Sahih (which leans upon such traditional sources for ambiguous passages) endorsed that option in its translation.

Ayat 52-55

Starting in ayah 52, God confesses that for every prophet He has sent down, Satan has always “thrown” something into the recitation. (I noted the word “thrown” because I enjoy the link in vocabulary to all the throwing done in Surah Ṭ H.) Then God abolishes/abrogates what Satan throws in and instates His verses. He lets this happen in order to test the believers, but particularly to test those who have unhealthy faith (“diseased hearts”) and to drive a schism between them and the real believers. This sounds incredibly dangerous, that God would encourage a schism in the community and also undermine the integrity of His scriptures, but it isn’t actually that dangerous in its own context. The schism is already perceived to be there, with the sick-hearted already amongst the people, and by widening it God is exposing those people as contaminants to be addressed. Also, this story demonstrates that God actively intervenes to protect His scriptures, as He does not allow the insertion to remain, and thus if you are a believer you have no reason to fear that other insertions remain elsewhere.

Where I thought this was going is that the test was to see if the people’s faith was strong enough to identify false teachings and be outraged at their presentation alongside sacred scripture. Such a test would demonstrate that the people are following the message because they can identify an aberration from an otherwise consistent message, thus strengthening the Quran’s testimony to be self-evident truth that brings men in direct contact with God. The result would be to prove that real believers are following the message, not the messenger. All other believers are just sheeple who trust in a man to mediate God to them.

However, the following ayat frame the entire event –the inclusion of false verses solely for the purpose of later removal– as a test that people are expected to accept on faith. This is shown particularly in ayah 54, where those who receive knowledge from God react to “it” (the test) by accepting, believing, and humbly submitting. “It” clearly is not a test of inserted verses, but rather their removal. This portrays that the whole upsetting event of adding and removing verses in the Quran was a test that need not bother the people if they are real believers. Ayah 55 continues that those who disbelieve will always be in doubt about the situation. With this in mind, I would redefine this section of ayat as starting at ayah 51, which denounces those who put effort into debunking (“cause failure”) to the scriptures. Inconsistency in presentation, with a batch of weak ayat getting removed in hindsight, is the kind of material needed for arguments that Muhammad was making the Quran up. By presenting the existence of such history as merely a test that the true believers won’t be bothered by, the Quran is disregarding the presence of such material as grounds for debate. To even debate it is to fail the test.

So is this section about any event in particular? Well, in tradition there is a story that, while preaching to a mixed assembly of Muslims and pagans, Muhammad was so passionate in his desire to reach his entire audience that he failed to catch the devil slipping a concession to the pagan pantheon into his recitation of the Quran. This insertion is known as the “Satanic Verses,” although tradition only remembers there being one verse. Wikipedia has a long article with the backs and forths of thoughts on this that you can read if interested. I’ve got lots of opinions about this tradition, but that takes me outside the surah. Please leave a question if you want to hear some, or comment about what you think!

Ayat 65

This is really a very small note. Just wanted to comment upon this ayah’s statement that God keeps the sky from falling upon the earth (except according to His permission). The concept of the sky falling is very much linked to ancient theories of the sky being a dome, like what I mentioned in Surah: The Prophets, Part 2. There still is flexibility in that samaa’ has many meanings, whether sky, firmament, or heaven. So this ayah is not robbed of meaning without a theory of the firmament and it now gets applied to ideas like space radiation or debris crashing into Earth.

Ayah 73

We still do not know how the Quran was assembled from quotes into suwar. Was all of Surah al-Hajj a continuous recitation? Or was it assembled from smaller fragments later? I ask this because there’s a curious contradiction of ideas in ayah 73. God mocks the reality of the pagan deities by saying they did not have enough power between them to even create a fly. The verse continues on to mock that if the fly took something from them, they would even be too weak to retrieve it.

…So the punchline is that they can’t take something from the very fly that they couldn’t create?

It’s kind of okay for the whole thing to be incoherent and nonsensical because the Quran wants to mock these deities as nonsensical. Still, that jump from “you can’t even create a fly” to “and if the fly…” made me wonder if this ayah was made of two similar quotes paired together. Both are about the gods being weak, and both feature a fly, but they aren’t really seamless as a continuous thought.

The Rhyming Scheme

There isn’t a full rhyming scheme in this surah, but there is a deliberate manipulation of language that reaches for the effects of rhyming. Almost every ayah in this surah concludes with a long, stressed syllable, always terminating in a consonant. For example there’s -iiq, -iid, -iiz, -uur, -uud, -aa’, -aar, to name a few. There is no rule or limit to what kinds of sounds are used, only that they carry the same syllabic feel. There certainly is no shortage of words ending with the long vowel+consonant ending in Arabic. Most plural nouns end this way, as do a good many adjectives (raḥiim, kariim, mubiin, ḥariiq, and such), as do present-tense-plural-masculine verbs. There are also a lot words to avoid, particularly most feminine words (which end in -ah), most other verbs, and pronouns, so it does still require manipulation to make your ayat end with the same syllabic feel.

I’m not fluent enough in Arabic to evaluate whether the surah had to use strange words or sentence structures to accomplish this rhyming scheme. I did notice that in some ayat where the verse could have potentially ended without the requisite syllable, an interjection was added to fill the need. For example, ayat 40-41 describe how God protects all those who remember Him; those who use their God-given authority to establish prayer, charity, and morality. Notice at the end of ayah 40 there is an interjection dividing the thought, and so it reads: God supports all those who support Him –Indeed, He is the Strong, the Mighty!– those who…etc. Without the interjection, ayah 40 would have ended with a pronoun suffix -hu, and thus would not have conformed to the quasi-rhyming of the surah. In the Quran’s context there is no such thing as an inappropriate time to commend God, so it is easy to insert an interjecting praise and thus the adjective ʕaziiz, “mighty,” brings the ayah into conformity. Ayah 41 also does not end its central idea with the proper syllable, and so it concludes with another interjection praising God, this one ending with a suitable plural noun. Were these interjections necessary? Couldn’t the ayat have been consolidated into one long ayah until they landed upon the proper conclusive syllable? Perhaps, but without knowing how the Quran was collated and how the ayat were differentiated, we can’t conclusively evaluate why it is arranged the way it is.

Quran Geek

It’s nice getting into the smaller suwar because I feel less pressure to skip interesting tibdits like these for the sake of keeping my posts contained and readable. I now almost blush at the fact that I covered Surah al-Baqara in only three posts way back in the beginning of this series. If I were to cover Al-Baqara now, given my established patterns and tendencies, I probably would have milked out no less than six posts, not to mention a trivia post or two trailing along behind it. That was a beast of a surah –too much too soon for me to get a handle on back then.

I also perhaps expected a few more comments and cohorts along the way than I have, and thus expected some of these things to come out in discussion with a readership. That also hasn’t happened, and I get it. These are long posts, they take a long time to read, and it also takes time to read along with the suwar and pick out these eccentricities. I do rather wish for a community to talk about this with though. To my current readers, thank you for spending time with me and reading my thoughts. Could you please recommend this series to someone around you who might also be interested? I would love to have a little thoughtful community form. In doing this, I’ve learned just how few people have read the Quran –even of those who have said they have– and just how few have even further read the Quran thoughtfully. I think that’s a shame, because even though I’m not particularly fond of the Quran’s view of the world, I do think that the very mind and viewpoint is still interesting to examine. I’m kind of a Quran geek.

And, well, what’s the point of being a geek without a geekdom?

A few remarks when it comes to Ayah 5 and gestation.

> a clinging thing

This is actually a “modern” translation of the word علقة. Originally, the word meant “blood clot”. You’ll find that in most of the older tafsir (exegesis) books. You can also see one of Mohammed’s companions explaining embryonic gestation (as was understood by Muslims of the time) and describing semen turning into blood before congealing to become a clot:

https://sunnah.com/urn/2202830

> I do not know historical theories of gestation (that information is harder to find than historical theories of cosmology) so I cannot confirm what the people around Muhammad’s time thought gestation involved.

The common idea at the time was that the father’s semen contained the whole essence of the child, which then grows withing the mother’s womb with little influence from her. There’s a famous story about Abu al-Aswad al-Du’ali (Arabic grammatist credited with adding diacritic marks to Arabic script) that he once had a fight with his wife over custody of their child so they went to a judge to plead their case. The wife claimed that she had the right since she carried the child to term. Abu al-Aswad retorted that he carried the child before her (eluding to the prevalent theory at the time). She amusingly replied that he discharged the seed with joy while she discharged the child with pain.

LikeLike

I thought about mentioning the word علقة but couldn’t come to a conclusion about it from my search of Lane’s Lexicon. The roots do seem to build towards words to do with clinging, but that’s not out of line with a clot. From my foreign vantage point it can be hard when seeing a long entry about “clinging things” to feel certain that “blood clot” (which I did see within the entry) was the intuitive meaning. Just like س ك ن build words like “house” and “rest” and then also “knife.”

LikeLike

You are so right about the difference between simply reading a holy text and reading it with intention. I find that I can almost feel the world they were written in and get lost for hours at a time. It’s an amazing experience. Thank you for this post.

LikeLike