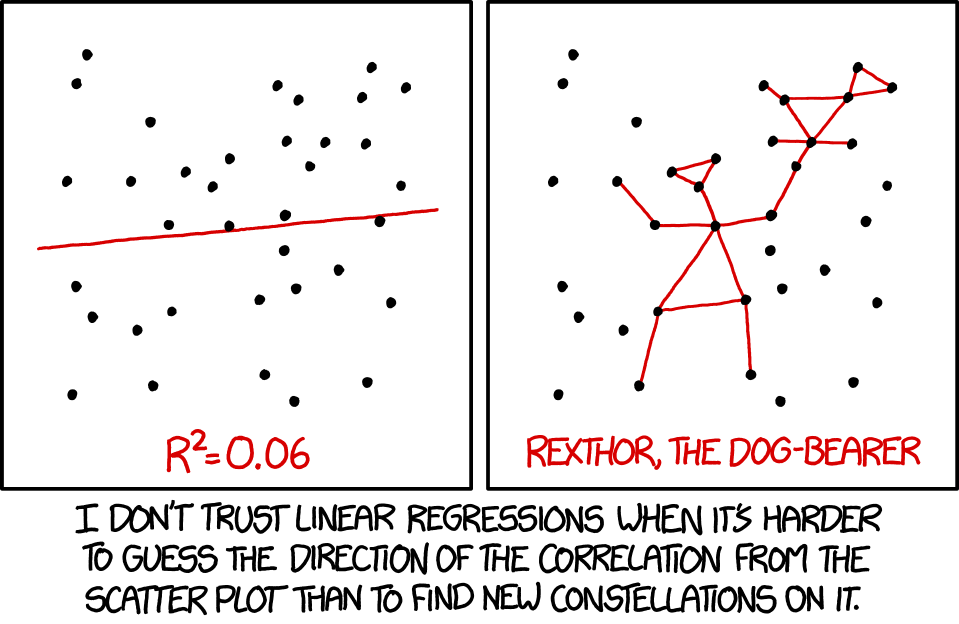

In The Women, Part 1 I devoted my time to examining the passages in this surah that dealt with social justice: inheritance, orphans, marriage, divorce, and general charity. Last week I looked at the passages that developed the standards of True Religion: devotion versus hypocrisy, belief in Divine Justice, doing good and avoiding sin (the worst sin being to misrepresent God), and the duty to fight oppression. That’s a lot of variety in one surah, laid out in a rather scatter plot way. Trying to prioritize information and draw thematic lines resembles solving those old math problems I hated.

Which am I doing? Read the 176 ayat and check my work.

Organizing all the bits and pieces of information takes a long time because it’s easy to start chasing threads into circles. One topic in this surah kept popping up as important to the other ones: the centrality of Muhammad as administering prophet. I couldn’t even mention it last week as was writing without exploding the post. So I reserved to for today, sharing space with some other miscellaneous material concerning Jesus as prophet, and prophethood in general.

Jesus as Prophet

I struggled with where to introduce this section, but decided to just place it up front in order to establish Jesus’s place in Islam’s prophets. That Jesus is only a prophet is not asserted by degrading any of his personality or character. When rebuking Christians for calling Jesus the Son of God, the Surah credits Jesus (and the angels) with being humble enough to take pleasure in relating to God as His servant. Changed instead are the details of Jesus’s birth and death. Previous passages have striven to rebuff that Jesus’s origins had any significance besides proving God’s power. This surah now rewrites the significance of Jesus’s death by denying he was ever crucified. Funnily enough, this story is retold not to correct the Christians, but the Jews. They are condemned for slandering Mary’s character and for claiming that they killed Jesus. It is revealed that the joke is on them, for they didn’t crucify him–not even kill him–and it was only made to look as though Jesus had been crucified (some translations favor the tradition that another person was made to look like Jesus and be crucified in his place). God certifies that they did not kill him, and we know from al-Imran that He instead assumed Jesus into His presence. This claim mostly shocks me because God perpetrated a lie upon the Jews in order to save Jesus, and misleads the Christians in consequence. Did God trick Jesus’s followers alongside the Jews?

The crucifixion of Jesus is perhaps one of the only historical facts we can know about him. Crucifixion was so notorious an execution method–more like being drawn and quartered than cleanly hanged–it is unlikely Jesus’s supporters would have invented, let alone embraced, such a discrediting penalty for their leader. Indeed, early Christians didn’t even depict the crucifixion but only recorded it through their writings. It wasn’t until later that poetic stylization of the event became fashionable in art, architecture, and jewelry.

Behold, the earliest depiction: a schoolboy’s slanderous graffiti. It says, “Alexamenos worships [his] God.”

Islam would say that historical records are based off of God’s deception and not the actual fact. Like much ancient history, perfect information for or against the crucifixion doesn’t exist, and since Jesus is so historically significant many scholars make their livings confirming or denying his factuality. There is room to question the facts, for sure, but for the sake of what I’m arguing I only need to confirm that Christians believed Jesus was crucified (1, 2). It is true that there are variant narratives offered in the Nag Hammadi anthology where Jesus is not crucified. Appeals to those sources must take into account Gnosticism’s proposed christology and theology (which in no way resemble that of general Christianity or Islam) before calling those communities lost or suppressed strains of true Christianity/Islam. There is little to no doubt that Christians have always believed in the crucifixion. It would be pretty hard to argue that God, in deceiving the Jews, didn’t also derail the Christians.

My intention is not to debunk this passage. There are articulate defenses of the Quran’s claims. I am instead questioning whether Islam regards Christianity as a valid religion when it rejects Christianity’s two formative facts –the godhood and crucifixion/resurrection of Jesus– and also whether they believe we were fooled by God’s own trickery. Judaism’s practices are in general more restrictive than Islam’s, I can see how Jews could operate within an Islamic community and not push boundaries. Christian practices tend to be much less restrictive than Islam’s and some even exceed Islam’s boundaries. Christian communities certainly did live, contribute, and thrive in Islamic societies, but I’m curious how they did not come at more odds with the condemnation of their beliefs and practices. I wonder if this idea that Christians believe a misdirection perpetrated by God Himself (who is “the best of schemers,”) made the Muslims more lenient to their perceived sins in times past.

So Islam’s Prophet Jesus (with our current data) is the same in virtue, still retains the title of Christ/Messiah, but is biographically different. He was born from a consecrated virgin, started teaching from infancy, performed miracles, taught reformation of religion and worship of The God, and was secretly “taken” into heaven with God while the world was mislead into believing he’d been horribly executed. His birth, life, and death have no significance elevating him above any other prophet. Being a prophet is already an exalted state, and one he was fully satisfied with. Having this biography in mind, let’s look at the line of prophets.

Nature and Chain of Prophethood

Historically speaking, Muhammad’s ministry most resembles Moses’s. He led people in a migration from oppression, delivered and adjudicated law, directed military actions, and revealed God to a people who maybe only had a vague or inaccurate conception of Him. His teaching also clearly resembles Jesus’s in that it focused more on securing the hope for a future life where all sources of pain will be removed. Any such similarities are taken to be a sign that Muhammad is only confirming the messages of the prophets before him, and that he is indeed just another prophet. This connection is supposed to be so obvious that those people who have already received Scripture (Torah and Gospel) are frequently rebuked for cynically rejecting Muhammad. A list of recipients of divine revelation are mentioned (Noah, unnamed others, Abraham, Ishmael, Isaac, Jacob, the Tribes, Jesus, Job, Jonah, Aaron, Solomon, David) as evidence that God has always been reaching out to mankind and thus men have no excuses for their failings. All of those messengers have to be believed in, or else you are rejecting guidance from God. Muhammad is just the latest in this chain.

From a Christian/Jewish perspective, this list is a bit odd. It doesn’t need to be comprehensive for the surah’s purpose, but the inclusion of certain people and the absence of others goads my petty nit-picks. Humor me for a paragraph. For Jews, the second most important prophet after Moses is Elijah, who hasn’t been mentioned yet. Maybe he’ll appear later? To not include him or any writers of the longest prophetic books (Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel) is odd considering figures like Job and Jonah are included. Job may have been a real person, it all depends who you ask, but his book of the Bible is categorized as philosophical poetry that questions the goodness and justice of God. Jonah, despite being a favorite Sunday school character, is nonetheless the lamest prophet in the Bible. I am rather fond of analyzing the Book of Jonah as a satire. Whether a real story or not, he is explicitly depicted as a miserable sample of humanity and religion.

While all prophets are to be accepted, we know from an ayah in al-Baqarah that God “makes some [prophets] exceed others.” This necessitates me articulating a traditional idea that is not self-evident in the Quran so far, but is illuminating: God rarely speaks directly to humans. Only Moses and Adam have been revealed to have spoken with God directly. Otherwise God supplies people with visions, dreams, or angels in order to communicate. In the case of the greatest prophets, God writes his messages for them in actual books, which are delivered by the angel Gabriel and declared by elect prophets. Moses received the tawraat (Torah), David the zabuur (Psalms), and Jesus the injiil (derived from the Greek word euangelion, “Gospel”). Although the word qura’an means “recite” and it was originally transmitted as an oral work, it always refers to itself as a book because Muhammad is understood to have memorized its passages from a divine book.

One way the Jews and Christians have challenged Muhammad, this surah says, is by asking him to bring down and physically show them the book he claims to be reciting. God sidesteps this request by recounting the story from al-Baqarah where the Jews demanded Moses to show them God directly. God had sidestepped that request back then by killing them all with lightening and resurrecting them. From al-Baqarah, we know the Jews almost immediately built the golden calf and sinned, so remembering such miracles here implies that they are worthless.

Prophets might be blessed in different ways, with some given greater responsibilities, but they are all united in function: to bring good news and warnings. God sends prophets so that people cannot claim ignorance for doing things God has deemed wrong, and are thus exposed for God’s justice. By claiming a lineage of prophets, Muhammad has historical precedence rather than miraculous evidence to authenticate his ministry. This is important, for besides revealing the Quran (and another event I’ll cover when we find it) Muhammad is not known to have performed any miracles.

Muhammad’s Vocation

I’m going to quote a long section of surah because the wording is striking and I want to call attention to it. I’ll write out ayah 59, and then 64-70. The quotes will be from the Sahih International translation, which prioritizes literal translation and sets apart its interpretive additions within brackets. I will bold ayah 65 because it is the one that really caught my attention:

O you who have believed, obey Allah and obey the Messenger and those in authority among you. And if you disagree over anything, refer it to Allah and the Messenger, if you should believe in Allah and the Last Day. That is the best [way] and best in result.”

God is charging the people to give Muhammad complete decisive authority. People are still accountable to other authorities (maybe on clan, tribal, local, business levels), but Muhammad supersedes them all regardless of the topic of dispute. The in-between passages condemn hypocrites who ask taghut sources for second opinions on Muhammad’s rulings.

“And We did not send any messenger except to be obeyed by permission of Allah. And if, when they wronged themselves, they had come to you [O Muhammad] and asked forgiveness of Allah and the Messenger had asked forgiveness for them, they would have found Allah Accepting of repentance and Merciful. But no, by your Lord, they will not [truly] believe until they make you, [O Muhammad], judge concerning that over which they dispute among themselves and then find within themselves no discomfort from what you have judged and submit in [full, willing] submission. And if We had decreed upon them, “Kill yourselves” or “Leave your homes,” they would not have done it, except for a few of them. But if they had done what they were instructed, it would have been better for them and a firmer position [for them in faith]. And then We would have given them from Us a great reward and We would have guided them to a straight path. And whoever obeys Allah and the Messenger – those will be with the ones upon whom Allah has bestowed favor of the prophets, the steadfast affirmers of truth, the martyrs, and the righteous. And excellent are those as companions. That is the bounty from Allah, and sufficient is Allah as Knower.

God swears by Himself that no one will be a believer until they accept Muhammad’s authority without doubts. The people are required to trust that Muhammad is infallible in his daily choices and rulings. If they do not have that trust, they are regarded as hypocrites. Muhammad and God’s name are so close to each other in phrases establishing functional authority. When repenting (probably of hypocrisy considering the prior verses), go to Muhammad to ask for God’s forgiveness and have him pray for you. When conflicted, take it before God and the Messenger. To go to heaven (or maybe to just receive full benefits of heaven), obey God and the Messenger. To obey the Messenger is to obey God (ayah 80).

I’m not saying that it isn’t clear that Muhammad is still subservient to God, only that it is clear how many magnitudes closer (in both function and knowledge) Muhammad is to God than the people are, and how centralized authority is around him. This surah confirms that Muhammad is both a religious and secular authority. He is understood to be transmitting more than general commands and ideals, but also judging specific daily circumstances of criminal justice, social welfare, and theological questions. A later verse adds that the oppressed people of the cities have been asking God to send them from Himself a Protector and Helper to end their oppression. It is clear that Muhammad is the intended answer to this prayer, giving him a messianic role as well.

These ideas circle around to inform my understanding of all the rest of this surah’s content, and much of our earlier material too. Muhammad is directly charged to act on God’s behalf in order to free the world of oppression. Muhammad has been transmitting laws, regardless of his experience or skills in the matter (since they are to have come from God), and these laws are to shape the society into one without oppression. Muslims are to take up fighting in order to defend this society and create a safe place for people to migrate to. They are not to oppress their neighbors by starting fights or turning away peace. People must migrate to the Messenger in order to seek shelter and purity in Islamic jurisdiction. Muhammad is the central actor in this ministry, and the pivot from which everything operates.

Islam without a Prophet

Muhammad’s centrality to Islam creates a conundrum. Despite the insistence in Surah al-Imran after the Battle of Uhud that Islam is independent of Muhammad, it kind of isn’t. Muhammad is at the center of a theocratic state, directing both religious and political action on God’s behalf. He has complete power and say. Once Muhammad died, there was a prophet-shaped hole left that no one could fill. How do you emigrate towards a dead prophet? How do you take your disputes before a dead prophet to receive God’s knowledge? How do you take your sins to the dead prophet to ask for God’s forgiveness? How do you run a theocratic government without a direct source of God’s input in your midst? How do you discern a holy war without God’s omnipotence declaring it to you? How do you trust an absolute authority whom you believe fallible? Who do you turn to when you and your friend disagree on the meaning of an ayah?

The Quran should be the source that fills that prophet-shaped hole, and within two decades of Muhammad’s death it was written down, assembled, and standardized. Its writing is understood to be the direct voice of God in a language they could understand. It should settle disputes, guide governments and wars, administer social justice, and teach religion. However, within its material there are still holes of information –such as those contradictions in the inheritance laws– and questions to be asked. The Arabic language has evolved past its historical roots and the old meanings are not so apparent as they once were. Since there is no prophet to turn to, academics must sift through accounts by Muhammad’s contemporaries to see how their prophet embodied the knowledge he was filled with. They must examine early tradition to see how the community Muhammad administered functioned. The writings of old scholars must be consulted in order to confirm the exact way an old word or phrase was comprehended in its time. Themes and morals must be distilled from other topics to be applied to things Muhammad’s contemporaries couldn’t imagine, such as birth control, weapons of mass destruction, and space travel. In this way, I find Islam to be like all other religions that base their faith off the material of a book from a past place and time.