Surah al-Anfal, “The Spoils of War.” In name and content, this surah is about battle and victory. Although not named, multiple ayat indicated to me that this surah concerns the aftermath of the Battle of Badr, an event which we already heard some about in Surah al-‘Imran: there is a caravan in a valley, a surprise meeting of armed forces, and a stunning victory. Surah al-‘Imran, if you’ll remember, was about the battle lost at the foot of Mt. Uhud, and it referenced the first victory at Badr to indict the Muslims of their failure. Because of that, I wonder why al-Anfal is placed after and thus far away from al-‘Imran. For Muslims reading according to the traditional 30-day Juz’ schedule, the messages are separated by five days. If al-Anfal and al-‘Imran had been placed one after the other, historical order of events would have been preserved, and the cautionary messages here would have combined with the reprimands in al-‘Imran into a very poignant joint reading.

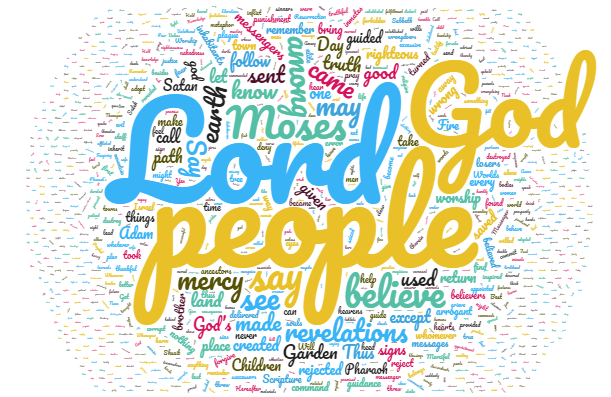

Despite being about a stunning victory, there are very few congratulations in Surah al-Anfal. Victory has brought loot, and loot has awakened divisions and a sense of entitlement amongst individuals. To employ an English turn of phrase, the spoils have spoiled things. Muslims are given permission to enjoy their victory, but always they are reminded that the victory belongs to God and to His Prophet. Authority is being reinforced, and the words “God” and “Messenger” appear in frequent parallel to drive home who has the authority.

Continue reading “Surah 8: The Spoils of War”